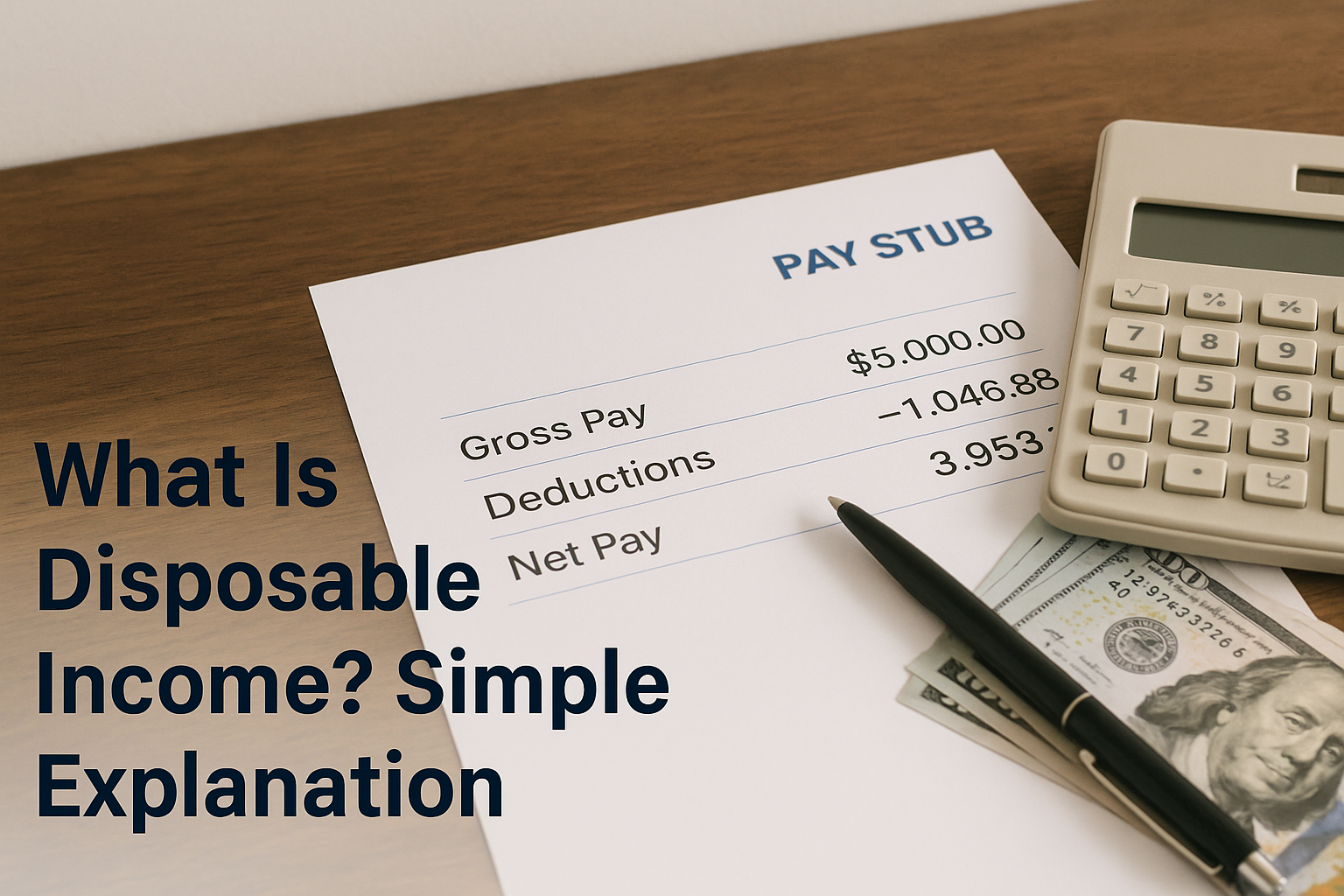

I remember the first “real” paycheck I ever got. After years of part-time gigs paid in cash, seeing that official paystub was a thrill.

And then, confusion.

The “Gross Pay” number was big and exciting. The “Net Pay” number—what actually hit my bank account—was… significantly less exciting. It was a financial buzzkill. I found myself staring at the list of deductions: Federal Tax, State Tax, FICA, Medicare, Health Insurance… and thinking, “Okay, so what money is actually mine?”

That’s the question, isn’t it? It’s the question that sits at the very heart of budgeting, saving, and just… well, living.

And it’s why we need to have a real talk about “disposable income.”

It’s a bit of a bureaucratic, cold-sounding term, isn’t it? “Disposable.” Like it’s trash you can just throw away. But in the world of finance, it’s the single most important number on your paystub.

Except… it’s probably not the number you think it is.

The Big Paycheck Disconnect

Here’s the disposable income explained in the simplest way possible: It is the total amount of money you have left after all mandatory taxes are taken out.

That’s it.

Gross Pay (what your boss says you make) – Taxes (what the government takes) = Disposable Income

This is the official, textbook definition used by economists and government agencies. It’s also called “Disposable Personal Income” or “Net Income.”

So, if you earn $60,000 a year, and you pay a combined $15,000 in federal, state, and local taxes (including Social Security and Medicare, which are mandatory taxes), your disposable income is $45,000.

But hold on. You’re probably thinking the same thing I did: “There is no way I have $45,000 to just ‘dispose’ of. I have rent. I have a car payment. I have to eat!”

And you are 100% correct.

This is the part where most people get confused. Honestly, it’s where I was confused for years. We hear “disposable” and we think “expendable.” We think it’s our “fun money,” the cash we can blow on vacation, video games, or a fancy dinner.

That is not what disposable income is. You’re thinking of something else.

The ‘Fun Money’ vs. The ‘Official’ Money

This is the most critical (and most overlooked) part of personal finance. You’re not trying to find your disposable income; you’re trying to find your discretionary income.

Let’s break this down with a real-world scenario.

Meet Sarah. She’s a graphic designer.

- Her “Vanity” Number (Gross Income): Sarah’s salary is $70,000 per year. This is the number she tells her friends, the number on her offer letter. It’s big and round and makes her feel successful.

- The “Involuntary” Deductions (Taxes): Before she sees a dime, the government takes its cut.

- Federal Income Tax

- State Income Tax (let’s say she lives in a state with one)

- FICA (This is your Social Security & Medicare contribution. It’s a tax.)

- Let’s say all these add up to $18,000 for the year.

- Her “Official” Number (Disposable Income):

- $70,000 (Gross) – $18,000 (Taxes) = $52,000

- This $52,000 is Sarah’s official disposable income.

This is the number economists care about. When they talk about “consumer spending,” they’re looking at this $52,000. It represents the total purchasing power Sarah has to dispose of into the economy—whether on rent, food, or shoes.

But Sarah still can’t just go buy a $52,000 sports car. Why? Because of her “Must-Haves.”

- The “Must-Haves” (Fixed & Necessary Costs): These are the bills Sarah has to pay to live her life.

- Rent: $1,500/month

- Utilities (Electric, Water, Gas): $150/month

- Car Payment + Insurance: $400/month

- Student Loan Payment: $200/month

- Groceries: $400/month

- Phone Bill: $80/month

- Total “Must-Haves”: $2,730 per month

- Her “Real” Number (Discretionary Income):

- First, let’s get Sarah’s monthly disposable income: $52,000 / 12 = $4,333 per month.

- Now, we subtract her “Must-Haves”: $4,333 (Disposable) – $2,730 (Must-Haves) = $1,603 per month.

This… this is the number you’re probably looking for.

This $1,603 is Sarah’s Discretionary Income. This is the “fun money.” This is what she has left over to choose what to do with. She can use it for:

- Savings

- Investing

- Going out to eat

- Netflix subscriptions

- Buying clothes

- Vacations

- Charity

So, why the two names? Think of it this way:

- Disposable Income is what you have left after the government is done with you.

- Discretionary Income is what you have left after your own life is done with you.

“Wait, What About My 401(k) and Health Insurance?”

This is another brilliant question and a super common pitfall.

“But wait,” you say, “my health insurance premium and my 401(k) contribution also come out of my paycheck. Aren’t those deducted?”

Here’s the tricky part: No.

When an economist or the IRS wants to calculate disposable income, they only subtract mandatory government taxes.

Your 401(k) contribution? That’s a choice. It’s a “voluntary” deduction. You are choosing to pay your future self. Your health insurance premium? Also technically a choice (though it rarely feels like it!).

So, to be a complete stickler for the rules: Gross Pay – (All Taxes) = Disposable Income

You then use your disposable income to pay for everything else: rent, groceries, and your 401(k), and your health insurance.

Does this distinction actually matter for your personal budget? Honestly, not really.

For your day-to-day budgeting, it makes far more sense to use your Net Pay (your take-home pay, what hits your bank) as your starting point. That number already has taxes, health insurance, and 401(k) contributions removed.

The only reason to know the “official” definition is to understand what people (and the news) are talking about. When you hear “consumer spending is up because disposable income rose,” they don’t mean everyone suddenly paid off their rent. They mean taxes went down or wages went up, leaving more money in that “post-tax” bucket.

The Disposable Income “Traps” (Real Mistakes People Make)

Knowing this number is great. But it’s how you use it that matters. I’ve seen people (and I’ve been the person) who fall into these traps.

Trap 1: The “My Paycheck is My Disposable Income” Illusion This is the most dangerous one. A freelancer gets a $5,000 check from a client. They think, “I have $5,000!” No, they don’t. They have $5,000 minus self-employment tax (a brutal 15.3%) minus federal and state income tax. They might only really have $3,000. Always, always budget based on post-tax money.

Trap 2: Forgetting the “Invisibles” Your monthly “Must-Haves” are easy to track. But what about the things you pay once or twice a year?

- Annual car registration

- Renter’s or homeowner’s insurance (if paid annually)

- Quarterly tax payments (if you’re a freelancer)

- That one streaming service you pay for yearly These “invisible” expenses are assassins for your discretionary income. They pop up, eat $500, and you have no idea where your “fun money” went. You have to account for them by setting aside a little bit each month (this is what a “sinking fund” is).

Trap 3: The Lifestyle Creep Monster This is the big one. You get a raise. Your Gross Pay goes from $70,000 to $80,000. Your disposable income goes up. Hooray!

So what do you do?

The wrong thing to do is immediately upgrade your “Must-Haves.” You get a more expensive apartment ($300 more), a new car ($200 more per month), and start eating out more ($100 more).

Suddenly, your $10,000 raise has vanished. Your disposable income went up, but your discretionary income—your actual freedom—stayed exactly the same. Or worse, it went down because you overspent.

This is a classic case of “lifestyle creep,” and it’s a monster that’s always hungry. The single best thing you can do when you get a raise is to pretend you didn’t. For at least 6 months. Take that new, extra discretionary money and route it directly to savings or high-interest debt. Give your brain time to catch up before your lifestyle does.

Okay, So How Do I Actually Use This Number?

Let’s stop talking about it and start using it. Forget the textbook definitions for a second. Here is the practical, human-sized process.

Step 1: Find Your “Real” Starting Number Grab your last paystub. Find the “Net Pay” or “Take-Home Pay.” This is your starting line. This is your actual disposable income plus your discretionary income, all in one pot.

Step 2: List Your “Must-Haves” (The Non-Negotiables) Open a spreadsheet or a notebook. List everything you must pay each month to survive and keep your job.

- Housing (Rent/Mortgage)

- Utilities (Electric, Water, Gas, Internet)

- Transportation (Car payment, gas, insurance, or public transit pass)

- Food (Groceries only. Not restaurants.)

- Debt (Minimum payments on student loans, credit cards)

- Insurance (Health, life, etc., if not taken from your paycheck)

- Basic Household Supplies (Toilet paper, soap, etc.)

Step 3: Do the “Freedom” Math Take your Monthly Net Pay (Step 1) and subtract your Total “Must-Haves” (Step 2).

The number you have left is your Discretionary Income. This is your “Freedom Fund.” It’s the only money you have true control over.

Step 4: Give Every Dollar a Job (The “Zero-Based Budget”) Now, before the month begins, you take that Freedom Fund and you assign it. You become the boss.

- $X to Savings

- $X to Investing

- $X to “Guilt-Free Spending” (restaurants, movies, clothes)

- $X to “That Annual Insurance Bill” fund

- $X to “Vacation” fund

You assign every single dollar until the Freedom Fund is at $0. Not because you’re broke, but because every dollar has a purpose.

This is how you turn a confusing term like “disposable income” into a powerful tool. It stops being a number that happens to you and becomes a number you control.

It’s not just an economist’s buzzword. It’s a map. It shows you the gap between what you earn and what you owe, and the space inside that gap is where you get to build your life.